Chapter of St. Víta

Chapter of St. Víta

Kneissl Family

Paul Family

Prückner Family

Wimmer Family

Schwarzenberg Family

Czechoslovakia

Dunn-Astley-Corbett Family

The origins of the present-day village are believed to date back to the reign of King John of Luxembourg in the early 14th century. At that time, the surrounding forests were royal property and served as a source of income for the crown. To make better use of these resources, the king is thought to have established a village originally named Tomášice, derived from the personal name Tomáš, in honour of the village’s founders—descendants of the royal chamberlain Tomáš.

On November 4, 1325, King John of Luxembourg granted Knight Chval and his son Dětřich the right to develope the village under German law, which clearly defined the lord’s rights and the serfs’ duties, preventing excessive burdens. The villagers valued this change so much that in 1534, they had it officially confirmed to prevent future impositions. Chval and Dětřich were allowed to bring in a baker, butcher, shoemaker, blacksmith, and miller, operate a tavern, and manage a hereditary reeve’s office without paying fees. They also received a garden and an equal-sized meadow with a forest, which they could clear and use as farmland.

Later, Domoušice came under the ownership of the Monastery of St. John on the Island near Davle, belonging to the Benedictine Order. In 1373, the monastery’s convent eased the burden of some taxes for the villagers and granted them the rights enjoyed by the town of Rakovník. Up until the Hussite Wars, the people of Domoušice held a significantly more favorable status compared to their neighbours.

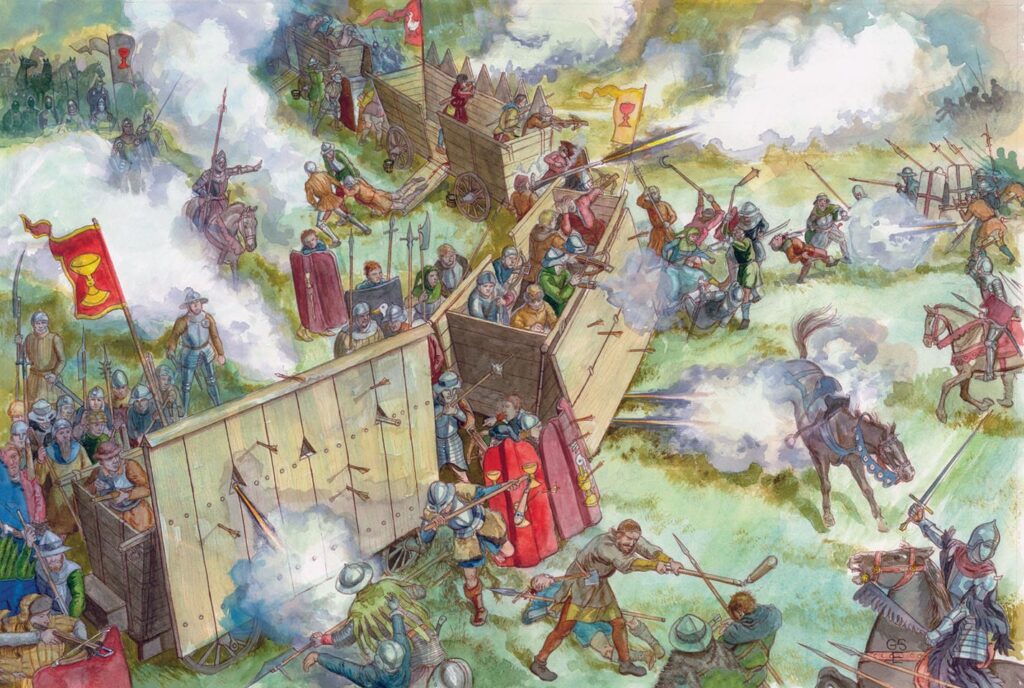

During the Hussite Wars, the lands of the Monastery of St. John were pledged to secular lords who had served Emperor Sigismund against the Hussites. Among these pledgeholders was Jindřich Žehrovský of Kolovrat, from whom the estate was redeemed in 1460. (Earlier, in 1420, Sigismund had pledged the lands to Jaroslav and Plichta of Žerotín for their support in the Battle of Vítkov.) In the second half of the 15th century, Domoušice remained under the Kolovrat family until 1460.

The next owner of Domoušice (or Domauschitz) became Jiří Bírka of Násilé, the governor of Křivoklát. After him, the estate passed to his son Václav. Since the time of the Hussite Wars, the local population adhered to the Protestant faith, which they maintained almost until the Battle of White Mountain. Domoušice was then placed under the administration of Prague’s New Town, which was to manage the Domoušice for the benefit of the Hospital of St. Alžběta in Prague. This arrangement lasted until 1627. In the same year, there was a report stating that a farmyard had been added to the local reeve’s office.

In 1627 Domoušice became the belonging of the deanery of St. Apollinaris in Prague. In 1628, it was transferred to one of the senior canons of St. Vitus, making the Metropolitan Chapter at St. Vitus Cathedral the official owner of Domoušice. The deans of the St. Vitus Chapter managed the estates, and the farmyard was sometimes rented out.

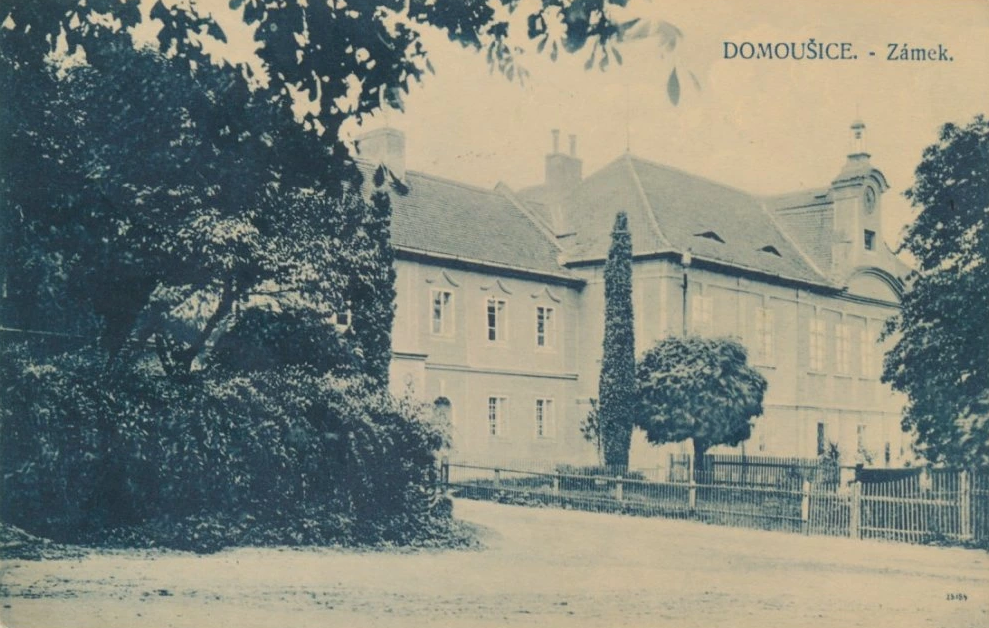

In 1712, the original farmyard was transformed into a grand Baroque estate. This upgrade included the “zámek” (chateau), spacious courtyard, barns, gardens, and other buildings, marking a shift from agricultural use to a more aristocratic and administrative function, solidifying the estate’s regional importance.

During this time the peasants faced increasing hardship, with the enforced “robota” (unpaid forced labour) growing more oppressive over time. Various patents from Emperor Leopold I, Charles VI, and Maria Theresa aimed to ease the burdens, but the situation remained difficult. Eventually, the Chapter decided to sell some of its smaller estates due to the growing challenges in managing them.

Domoušice was sold in 1754, to the dean of St. Vitus, Jan Ondřej Kneisl. At that time, the estate included 14 full-time and 12 part-time farmers. Records indicate that Kneisl had the local church renovated and expanded. After him, the estate was inherited by his nephew, Jan Augustin Kneisl. It was he who violated the imperial labor patents and burdened the people of Domoušice to such an extent with the unlawful “robota” (unpaid forced labour) that they rebelled against him and joined the “Peasant revolt of 1775”.

Jan Augustin Kneisl fell into debt, and in 1783, Domoušice was sold to Wenzel Johann Paul, a sworn imperial-royal accountant and inspector for Count Clam-Gallas. In 1785, he founded a new part of the village called Filipov. Wenzel’s son and heir, Leopold Paul, who was also a steward for Count Clam-Gallas, officially took over Domoušice in 1790. However, nine years later in 1799, he sold the estate to Karl Prückner who then sold it three years later to Baron Jakub Wimmer of Wimmer.

Later that same year in 1802 he sold it to Prince Joseph of Schwarzenberg – one of the biggest land owners in the country. Thereafter, the entire estate was merged with the neighboring Citoliby domain. Domoušice was renovated and retained as an independent forestry office, whose administrative district included forests from several surrounding estates owned by Prince Schwarzenberg.

After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the founding of Czechoslovakia in 1918, the new government launched a major land reform aimed at breaking up the vast estates held by the old aristocratic families. This reform, implemented in stages through the 1920s, forced large landowners—like Prince Schwarzenberg—to give up much of their property, which was redistributed to small farmers, war veterans, and local communities in an effort to create a more equal and self-sufficient society.

As part of this reform, the Domoušice estate was transferred to the State Forest Administration in 1924. It remained under state control for decades: the chateau partly served as offices for forestry officials, the barns were used by the local agricultural cooperative (JZD) during the nazi occupation and communist era, and the main wing of the Chateau was converted into flats.

Following the Velvet Revolution in 1989 and the return of private property rights, the Chateau was eventually privatized. In 2002, it was purchased in its post communistic state by the Dunn-Astley-Corbett family, who continue to revive it to its former state to this day.